Defense & Security

Between War and Agreement with Lebanon: The Conflict Over the Land Border

Image Source : Shutterstock

Subscribe to our weekly newsletters for free

If you want to subscribe to World & New World Newsletter, please enter

your e-mail

Defense & Security

Image Source : Shutterstock

First Published in: Feb.28,2024

Apr.05, 2024

Demarcating the land border between Israel and Lebanon is an important and necessary step—but is it right to do under fire? In this document, INSS researchers provide an answer to this question and detail the background and points of disagreement between the two countries on this issue As part of the American-led efforts to use diplomatic means to end the fighting that has been ongoing for nearly five months between Israel and Hezbollah, the need to demarcate an agreed-upon border between Israel and Lebanon was also on the agenda. The Lebanese government is eager to include border demarcation in any ceasefire agreement and has adopted the same policy on this matter as Hezbollah, linking an end to the fighting to the cessation of Israeli operations in the Gaza Strip and presenting a hardline maximalist approach to border demarcation. Negotiations over the land border between the two countries are likely to be exhaustive due to the complexity of the issue and the wide gaps between the sides. It would be wrong, therefore, to conduct them under fire. At the same time, as part of an agreement to end the conflict, it is feasible to include an agreement over the establishment of a mechanism to discuss the issue at the next stage—once the fighting on the Israel–Lebanon border has died down. Increasingly concerned that the fighting between Israel and Hezbollah could escalate further and turn into an all-out war, the United States is working to advance a diplomatic move that would lead to a ceasefire. France, and more recently the United Kingdom and Germany have joined the Americans in this effort. The Americans have entrusted the task to US President Joe Biden’s close adviser, Amos Hochstein, who successfully brokered the maritime agreement between Israel and Lebanon, which was signed in October 2022. At the behest of the Lebanese, Hochstein has been trying over the course of the past year to recreate this success and to get the parties to agree to a permanent land border. Thus far, he has not been successful. Beirut recently raised again the issue of demarcating the land border between Israel and Lebanon in the framework of efforts to secure a ceasefire between the IDF and Hezbollah, which have been engaged in limited combat along Israel’s northern border since Hezbollah initiated the conflict on October 8. The fighting has been ongoing since then, in parallel to the war in Gaza. In their discussions with American officials, acting Lebanese Prime Minister Najib Mikati and his foreign minister, Abdallah Bou Habib, have been pleased by the Biden administration’s willingness to help broker a ceasefire and to restore quiet to southern Lebanon. They say that they are committed to a diplomatic solution and to international decisions, with an emphasis on UN Security Council Resolution 1701. At the same time, they have taken a hardline position and have been forced to toe the Hezbollah line. They have done so not only in terms of linking an end to the fighting on the Lebanon border with a cessation of IDF operations in the Gaza Strip but also in terms of their demands when it comes to demarcating the land border. Their opening position is intransigent. In their diplomatic meetings and in interviews they have given to the media, both Mikati and Habib have raised the demand that Israel withdraws from every inch of Lebanese territory and, at the same time, they speak about the Mandate-era border, which was adopted as part of the 1949 Armistice Agreements, as the reference point rather than the Blue Line, the line of withdrawal identified in 2000 by the United Nations, without prejudice to any future border agreement. Reports in the Israeli and Lebanese media suggest that the issue was also raised during Hochstein’s recent visits to Israel (on January 4 and again on February 4) and Beirut (on January 11), but for the time being, Hezbollah and, in its wake, the Lebanese government are adamant that they will not pursue a diplomatic channel as long as the war in Gaza is ongoing.

The border between Israel and Lebanon, which is around 120 kilometers in length,[1] was demarcated more than a century ago as part of the Franco–British Agreement on Mandatory Borders that was signed in Paris in December 1920. That agreement saw the two European superpowers divide up the territory of the Ottoman Empire between them and agree on the borders between both Lebanon and Syria (readers must understand that it was not between Lebanon and Syria specifically, but between the territory of both and Palestine), which were under the French Mandate, and Palestine, which was under the British, from the Mediterranean Sea to Hama (which now makes up the border triangle between Israel, Syria, and Jordan). The agreement drew out the general path of the border, and the sides agreed to set up a joint commission to demarcate the exact path of the border. The commission was headed by two officers—French Lieutenant Colonel Paulet and British Lieutenant Colonel Newcombe. The commission demarcated the border, and in March 1923, the final agreement was approved by both countries. It was ratified in 1935 by the League of Nations. The system used by the commission to demarcate the border—a process that took an entire year and which left behind meticulous documentation of its work—was old-fashioned and problematic; it led to huge inconsistencies in the border. The border they drew up did not fully correspond to the border that was agreed on in Paris in 1920, but it was marked on the ground using piles of rocks. These piles were eventually replaced by 71 posts known as boundary pillars (BPs), of which 38 were placed along the Israel–Lebanon border. It should be noted that most of these BPs disappeared or were destroyed, making later demarcation difficult. Throughout the Mandatory period, right up until Israel and Lebanon gained their independence, the boundary drawn up by the commission was recognized as the international border. It was also the boundary that was used for the March 1949 Armistice Agreement between Israel and Lebanon. That agreement, which the Lebanese are citing as their reference point for demarcation today, was not a detailed demarcation of the boundary. Rather, the agreement merely stated that the “armistice line will run along the international border.” In other words, along the border that was drawn up by the two Mandatory powers and approved in 1923.[2] Following the withdrawal of the IDF from Lebanon in May 2000 and as part of the implementation of Security Council Resolution 425 (1978), the United Nations tried to demarcate the IDF’s withdrawal line using a team of its own cartographers. They drew what became known as the Blue Line, which deviates in several points from the Mandate-era boundary, and they based it on cartographic data and the interpretation thereof by members of the team. Israel and Lebanon both accepted the Blue Line as the line to which IDF forces would withdraw from southern Lebanon, but Lebanon submitted reservations that turned into points of contention between the sides. The UN approach is to recognize a border line upon which both parties will agree, although it is doubtful that Lebanon will agree to the Blue Line as the basis and likely will insist on the 1949 line. After the 2006 Second Lebanon War, Israel and Lebanon agreed to physically demarcate the Blue Line on the ground, and to this end, a professional committee was formed. This committee determined the exact location of 470 reference points along the Blue Line—around four such points for every kilometer. The goal of marking the border using blue barrels was to make the border clear to the local population, to military personnel, and to the United Nations—and to prevent any inadvertent Blue Line crossings or violation. Thus far, however, barrels have only been placed on around half of the reference points (more than 270). Each of them was only placed after Lebanon and Israel had examined its exact position and given their approval.

After the delineation and demarcation of the Blue Line, Lebanon presented reservations regarding 13 points along the Blue Line, covering an area of 485,000 square meters (not including the territory in the triangle of borders with Syria beyond the 1949 Armistice Line). To this day, this remains the main point of contention between the two countries. According to the Lebanese, these points deviate from the boundary that was determined in the 1949 Armistice Agreement (see the map in Appendix A). These points have been discussed at length over the years in contacts between the sides as part of the tripartite meetings and coordination mechanism established by UNIFIL. On a number of occasions, there were even reports that they have reached understandings about a solution for seven of them (although there has been no official announcement that they have been resolved). In July 2023, before the outbreak of the current conflict, the Lebanese foreign minister claimed that of the 13 contested points, agreement had been reached over seven, and that there were only six left to be resolved. Two months later, however, the Lebanese army issued an official statement in which it said that it still sees the 13 as being violations by Israel (the Lebanese see the territory on their side of the 1949 Armistice Line and the Blue Line as having been occupied by Israel) and that nothing had been finalized on the matter. Moreover, the army said representatives in the tripartite coordination mechanism did not have the authority to approve this. Recently, against the backdrop of negotiations, the issue was again raised in an interview given by Mikati. On February 1, he claimed that seven of the 13 points had already been settled, but that there were still major gaps in the positions of both sides with regard to the remaining six. Five days later, the foreign minister made a similar argument. The table below shows the 13 contested points, most of which could be resolved with some good will from both sides. At the same time, a number of points of strategic importance will be hard to resolve—primarily the first point close to the coast at Rosh Hanikra (B1), given its strategic location and its importance to both sides. This was one of the reasons that Israel demanded within the maritime agreement to preserve the status quo at this particular point, which was initially intended to be the starting point for the maritime demarcation, and to postpone the discussion on it until negotiations took place over the land border.

According to some recent reports, in addition to the 13 familiar points, Lebanon has already presented more Israeli violations and has demanded that Israel withdraw from 17 other areas beyond the Blue Line, some of which correspond with the 13 previous areas of contention. This is in contrast to the recently stated position of the Lebanese prime minister and foreign minister, both of whom referred only to the 13 contested areas. Details of these points, as published by the Hezbollah-affiliated Al-Akhbar newspaper, appear in Appendix B. In addition to the points of contention along the Israel–Lebanon border, there are also a number of substantial contested points on the Golan Heights. The Lebanese have laid claim to areas that were captured by Israel from Syria in 1967 during the Six-Day War in the border triangle between Israel, Lebanon, and Syria. According to Beirut, Israel must return these territories, which it claims as its own, before any resolution of the conflict with Syria, which has opted not to deal with the issue at the current time. Further complicating the situation in these areas is the Golan Heights Law that Israel passed in 1981, which formalized the change in the legal status of the Golan and determined that the area fell under Israeli law, jurisdiction, and authority. These disputes form a major part of Hezbollah’s narrative. The organization argues that it is fighting for the liberation of more Lebanese territory from Israeli occupation, while exacerbating the already intense disputes between Beirut and Jerusalem and using them as part of its struggle against Israel. Therefore, it is no coincidence that many of Hezbollah’s military attacks during the past nearly five months of fighting have also been directed at the areas of Mount Dov and Shebaa Farms. There are two main areas in question: The northern part of the village of Ghajar: Lebanon claims sovereignty over the northern part of the village, which is located on the original border between Syria and Lebanon. Indeed, Lebanon’s claim is not entirely groundless, since the Blue Line dissects the village, in accordance with the findings from 2000 by UN cartographers, who worked according to maps in their possession. The northern part of the village, therefore, is in Lebanese territory, even though it was captured by Israeli forces from Syria in 1967 and its residents are Alawites. Lebanese complaints intensified after September 2022, when Israel erected a fence to the north of the village to prevent infiltrations from Lebanon. The erection of this fence was done in coordination with the IDF, which took into account the residents’ suffering from having their village split in two and the fact that entry was only possible via a border police and military checkpoint. Closing off the village from the north allowed it to open to visitors. In addition to the northern section of the village, Lebanon is also demanding territory to the east of the village. The Shebaa Farms: This is an unpopulated agricultural area on Mount Dov (the foothills of Mount Hermon), between the village of Ghajar and the Lebanese village of Shebaa (in the border triangle), which Beirut claims belongs to the village. From an Israeli perspective, this strategic area is vitally important in order to monitor a hostile region. Evidence of this was provided in October 2000, when three Israeli soldiers were abducted in a cross-border raid. It is no coincidence that Hezbollah’s first attack during the current conflict, on October 8, was against Mount Dov, which has become a key target over the past months. In contrast to the official Lebanese position, Hezbollah also has claims to more Israeli territory, which it wants to “liberate from occupation.” There are seven Shiite villages in the Upper Galilee which were abandoned or evacuated, and then captured by Israel during the War of Independence in 1948. It should be stressed that in official statements from Beirut about the border dispute with Israel, these villages are not mentioned. However, it is likely that, even after the resolution of the dispute over border demarcation between the two countries, Hezbollah will continue to refer to these villages as occupied Lebanese territory. This is an integral part of its efforts to maintain its status as “defender of Lebanon” and it will be used to incite hostility toward Israel. From an Israeli perspective, it would be wrong to negotiate the border demarcation under fire. The issue of border demarcation has, as mentioned, come up as part of the diplomatic efforts to end the fighting between Hezbollah and Israel; the Lebanese side (and, it seems, the mediators) raised it as one of the things that Israel could offer in order to promote a ceasefire. However, given the ongoing escalation and the possibility of all-out war, it appears that it would not be the right course of action for Israel to include negotiations over the future land border in talks aimed at securing a ceasefire—notwithstanding the importance of an agreed-upon resolution of the issue. There are several reasons for this: The time element: Negotiations are likely to be long and complex, given the profound disagreements that exist, especially over three points: Rosh Hanikra (B1); the village of Ghajar; and the Mt. Dov/Shebaa Farms. Such talks will not be completed quickly and will not lead to a ceasefire any time soon, especially given that the Lebanese side is currently presenting a particularly hard line. Israel, on the other hand, is interested in an immediate end to the fighting, so that the evacuated residents of the North can return to their homes as soon as possible. This argument is also supposed to convince the Americans, who are also keen to secure a ceasefire sooner rather than later and to avoid regional conflagration. An achievement for Hezbollah and the loss of a bargaining chip: If Israel were to hand over territory to Lebanon—no matter how little—as a result of the current conflict, it would inflate Hezbollah’s sense of accomplishment, as well as its claimed status as the ‘protector of Lebanon.’ It would also strengthen its argument to remain an armed organization, against the wishes of those citizens in Lebanon who want it to turn over its weapons to the Lebanese army. Moreover, Israel would lose a bargaining chip in the anticipated negotiations over the implementation of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, especially in terms of its desire for Hezbollah to withdraw north of the Litani River. The same is true of a partial solution, regarding, for example, the seven border points over which there is agreement in principle. While Hezbollah would portray this as a “victory,” the disagreements and the reasons for continued conflict would remain unaddressed. There is no official address on the Lebanese side with which Israel can sign any agreement, given the political vacuum that exists there. Since the last election in Lebanon, in May 2022, a transitional government has been in power and, since the end of President Michel Aoun’s term of office in October 2022, Lebanon has yet to elect a replacement. As per the constitution, it is the Lebanese president who has the authority to sign such agreements; indeed, it was Aoun who signed the maritime border agreement with Israel on his last day in office. Similarly, opponents of any agreement with Israel could challenge the authority of the current interim government to engage in negotiations on any issue with Israel. In conclusion, reaching an agreement on the route of the land border between Israel and Lebanon would be an important element in forging a new reality in the region. However, it would not be right to hold a complex discussion on the issue, and certainly not to accept a partial agreement that would include Israel’s surrendering of territory, as long as Hezbollah has not agreed to cease the current fighting, which it initiated. Therefore, Israel must reject the inclusion of the issue in the preliminary understandings over a ceasefire and must insist that negotiations over the demarcation of the land border only take place at a later stage.

Note: These are areas that Israel currently occupies and which the Lebanese claim violate the Blue Line. This list was published on September 7, 2023, by the Al-Akhbar newspaper, which is affiliated with Hezbollah. [1] “It’s time to talk about the Blue Line: Constructive re-engagement is key to stability,” March 5, 2021, https://unifil.unmissions.org/it%E2%80%99s-time-talk-about-blue-line-constructive-re-engagement-key-stability [2] Haim Srebro, True and Steady: Mistakes in the Delimitation of the Boundaries of Israel and Their Correction (Tzivonim Publishing, 2022), p. 143.

First published in :

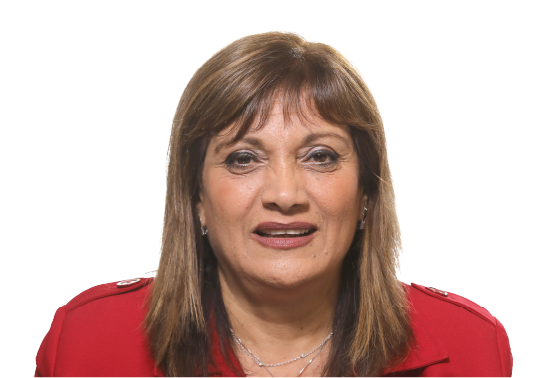

Orna Mizrahi, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies, joined INSS in December 2018, after a long career in the Israeli security establishment: 26 years in the IDF (ret. Lt. Col.) and 12 years in the National Security Council (NSC) in the Prime Minister's Office (she served under 8 heads of the NSC). In her last position (2015-2018) as Deputy National Security Adviser for Foreign Policy, she led strategic planning on regional and international policy on behalf of the NSC for the Prime Minister and the Israeli Cabinet, and was responsible for preparing the papers for the Prime Minister's meetings with leaders in the international arena. During her service in the IDF she served as an intelligence analyst in the Military Intelligence Research Division and as a senior officer in the Strategic Planning Division. She specialized mainly in research and strategic planning on regional issues, with an emphasis on the countries of the first circle and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Ms. Mizrahi holds an M.A. (cum laude) in History of the Middle East from Tel Aviv University and two B.A. degrees from Tel Aviv University: one in History of the Middle East and the other in General History and the Bible (summa cum laude). She is active in Forum Dvorah, which promotes the inclusion of women in the political-security establishment.

Lt. Col. (res.) Stéphane Cohen is a researcher at the INSS - Syria and Lebanon research program. Raised and hardened in the rural countryside of Burgundy, France, Cohen moved to Israel at eighteen and filled several IDF positions in the Israeli Air Force and the International Cooperation Unit. His last position was commander of the IDF liaison unit to the UN forces in Syria, Lebanon, and Israel. Cohen has received multiple awards for outstanding service, including the State of Israel President's Award and the Israel Air Force Excellency Decoration. Until 2017, Cohen served as the Director of the Diplomatic Program at The Israel Project (TIP), a non-profit organization based in Washington and Jerusalem that provided facts to policymakers, the press, and the public on issues affecting Israel and the Middle East. Cohen has a B.A. in Political Science and International Relations from the Open University of Israel (2011) with honors, an M.A. in Security and Diplomacy from Tel Aviv University (2014), and graduated from the UN Military Observers Course (2006). Cohen has contributed to various scholarly publications, including the Israel Journal of Foreign Affairs, Moshe Dayan Center for Middle Eastern and African Studies, and IPS - IDC's Journal for Policy and Strategic Affairs.

Unlock articles by signing up or logging in.

Become a member for unrestricted reading!