Europe’s Demosthenes moment: putting defence at the centre of EU policies

by Josep Borrell

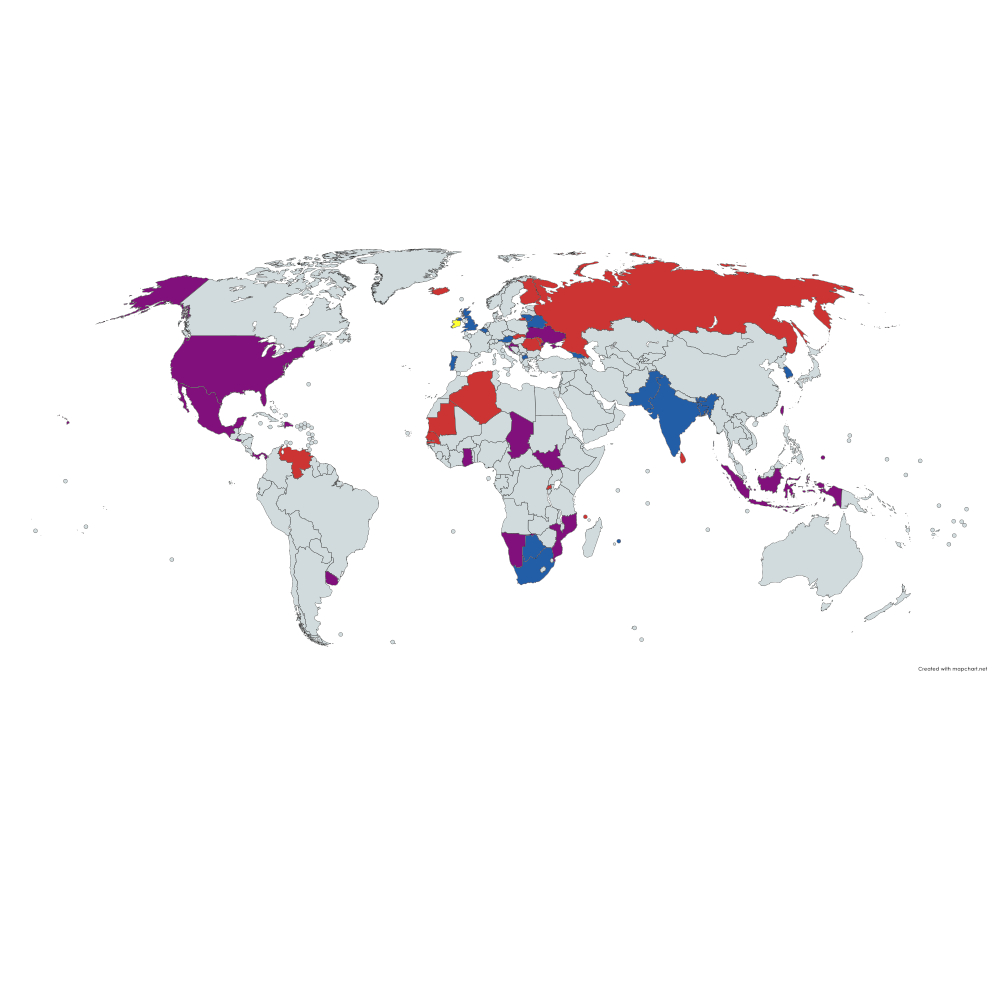

HR/VP blog – Defence was at the centre of the last European Union Council. This was the culmination of intense work on EU’s security and defence with the preparation of the European Defence Industrial Strategy and the creation of a new fund to step up our military support to Ukraine. We took stock also of the progress made in implementing the Strategic Compass. Power politics are reshaping our world. With the Russian war of aggression against Ukraine, the war that has flared up again in the Middle East, coups in the Sahel, tensions in Asia… we witness at the same time the return of ‘old’ conventional wars and the emergence of ‘new’, hybrid warfare characterised by cyberattacks and the weaponisation of anything, from trade to migration. This deteriorating geopolitical environment is putting Europe in danger, as I anticipated when presenting the Strategic Compass, the new EU Defence and security strategy, in 2022. Four years ago, when we were facing the COVID-19 pandemic, many said that the EU was living a Hamiltonian moment because we decided to issue a common debt to alleviate the consequences of this crisis as Alexander Hamilton did after the US independence war. We are now probably entering a Demosthenes moment, in reference to the great Greek politician mobilising its fellow Athenian citizens against Macedonian imperialism 2400 years ago: we are finally becoming aware of the many security challenges in our dangerous environment. What are we doing to address these multifaceted threats? The month of March marks two anniversaries: the third of the creation of the European Peace Facility (EPF) and the second of the adoption of the Strategic Compass. These tools have been central to our geopolitical awakening during the last years. It is the right moment to reflect on what has been done and where we are heading on security and defence. Supporting Ukraine militarily in an unprecedented way The European Peace Facility (EPF) is an intergovernmental and extra-budgetary EU fund. It was established in 2021 to allow us to support our partners with military equipment, which was not possible via the EU budget. We started with €5 billion, today the financial ceiling of this fund stands at €17 billion. While it was not originally created for this purpose, the EPF has been the backbone of our military support to Ukraine. So far, we have used € 6.1 billion from the EPF to incentivise the support to Ukraine by EU Member States and, with them, the EU has delivered in total € 31 billion in military equipment to Ukraine since the beginning of the war. And this figure is increasing every day. Thanks to these funds, we sustained our military support to Ukraine. Among other actions, by this summer, we will have trained 60.000 Ukrainian soldiers; we have donated 500.000 artillery shells to Ukraine and by the end of the year it will be more than 1 million. Additionally the European defence industry is also providing to Ukraine 400.000 shells through commercial contracts. The Czech initiative to buy ammunition outside the EU comes in addition to these efforts. However, it is far from being enough and we have to increase both our capacity of production and the financial resources devoted to support Ukraine Last Monday at the Foreign Affairs Council, we have decided to create a new Ukraine Assistance Fund within the EPF, endowed with € 5 billion, to continue supporting Ukraine militarily. I have also proposed last Wednesday to the Council to redirect 90% of the extraordinary revenues from the Russian immobilised assets into the EPF, to increase the financial capacity of the military support for Ukraine. Reinforcing our global security and defence partnerships But the European Peace Facility does not only help Ukraine. So far, we have used it to support 22 partners and organisations. Since 2021, we have allocated close to €1 billion to operations led by the African Union and regional organisations, as well as the armed forces of eight partner countries in Africa. In the Western Balkans, we are supporting regional military cooperation, as well as Bosnia and Herzegovina and North Macedonia. We are also supporting Moldova and Georgia in the Eastern neighbourhood, and Jordan and Lebanon in the Southern Neighbourhood. Since the beginning of my mandate, we have launched nine new missions and operations under our Common Security and Defence Policy (CSDP). The last one, Operation ASPIDES in the Red Sea and Gulf region to protect commercial vessels, has been set up in record time. With operations Irini in the Mediterranean, Atalanta near the Horn of Africa and our Coordinated Maritime Presences in the Gulf of Guinea and the Indian Ocean, we are becoming more and more a global maritime security provider. We launched also last year two new civilian missions in Armenia and in the Republic of Moldova. However, our missions in Niger had to be suspended due to the military coup and our military mission in Mali has been put on hold. We are currently reconsidering the form of the support we can offer to our partners in the region: in this context, we have set up last December a new type of civilian-military initiative to help our partner countries in the Gulf of Guinea fight the terrorist threats stemming from the Sahel. We have also reinforced our cooperation with NATO in various key domains such as space, cyber, climate and defence and critical infrastructures. We have broadened and deepened our network of tailored bilateral security and defence partnerships with Norway, Canada, as well as countries in the Eastern neighbourhood (Georgia, Moldova), Africa (South Africa, Rwanda), Indo-Pacific (Japan, Republic of Korea, Australia) and Latin America (Chile, Colombia). The first Security and Defence Schuman Forum in March last year, bringing together security and defence partners from more than 50 countries, was a success. We will build on this when we meet for the next Schuman Forum on 28 and 29 May. Enhancing the capacity to react to crises abroad One of the main deliverables foreseen by the Strategic Compass was the creation of a new EU Rapid Deployment Capacity to be able to quickly react autonomously to crisis situations, for instance to evacuate Europeans in case of an emergency like in Afghanistan in August 2021 or in Sudan in April 2023. It will become operational next year, but to prepare for it, we organised the first ever EU military Live Exercise last October in Cadiz, in Spain. It involved 31 military units, 25 aircrafts, 6 ships and 2,800 personnel form Member States’ armed forces. A second Live Exercise will take place at the end of the year in Germany. A new Crisis Response Centre is also now operational in the EEAS to coordinate EU activities in case of emergencies, including the evacuation of European citizens. We are also strengthening our military and civilian headquarters in Brussels. Investing more in defence together and boosting the EU defence industry At home, we need also to invest much more and help our defence industry to increase its production capacities. There is no other solution if we look at the magnitude of the defence needs for Ukraine but also for our Member States that need to replenish their stocks and acquire new equipment. EU Member States are already spending significantly more on defence with a 40 % increase of defence budget over the last ten years and a € 50 billion jump between 2022 and 2023. However, the € 290 billion EU defence budget in 2023 only represents 1.7% of our GDP under the 2% NATO benchmark. And in the current geopolitical context, this could be seen as a minimum requirement. However, the global amount of our expanses is not the only figure we have to follow carefully. To use our defence expenses efficiently, we have also to take care of filling gaps and avoiding duplications. As I have already said in many occasions, we need to spend more but also better, and better means together. In 2022, the European armies have invested 58 billion in new equipment. For the fourth year in a row, it exceeded the benchmark of 20 % of the defence expenses. However, only 18% of these defence investments are currently done in a collaborative manner, far below the 35% benchmark set by EU Member States themselves in 2007. Since the start of the Russian war of aggression, 78 % of the equipment bought by EU armies came from outside the EU. We are also lagging behind in our investments in Research and Development. That is the reason why I presented earlier this month together with the Commission the first-ever European Defence Industrial Strategy. We need to incentivise much more joint procurement, better secure our security of supplies, anchor the Ukrainian defence industry in Europe and organise a massive industrial ramp-up. We also need to catch up on new military technologies like drones or Artificial Intelligence. With its innovation hub, the European Defence Agency will continue to play a key role in these efforts. To succeed, we will need to ensure much better access to finance for the European defence industry, notably by adapting the European Investment Bank lending policies. We should also foresee issuing common debt to help finance the major necessary investment effort in defence capabilities and defence industry, as we did to face the COVID-19 crisis. However, we have still a lot of work to do to reach an agreement on that subject. Finally, we will also need to reinforce our defence when it comes to hybrid and cyber threats, foreign information manipulation and interference and resilience of our critical infrastructure. As detailed here, a lot has already been done in recent years, however I am very much aware that a lot more remains to be done to match the magnitude of the threats we are facing. We need a leap forward in European defence and European defence industry.