Ten Things to Watch in the Middle East and North Africa in 2024

by Prof. Dr. Eckart Woertz , Olena Osypenkova

Less than two years after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Gaza War has re-ignited the Israel–Palestine conflict and disrupted regional politics. Developments in Syria and Yemen are in flux, Egypt finds a new role as mediator, and new spaces are opening up for international actors like China. We present a list of ten things to watch in the region as we move into 2024.

Local conflicts: Authoritarian resilience will likely manifest itself in a series of sham elections. The Yemen War might linger on amid negotiations, while Israel has no plan on how to run Gaza after an end to hostilities.

Regional developments: The Arab League has brought Syria back in from the cold. Israel’s normalisation of relations with Arab countries is on hold for the foreseeable future. Egypt is regaining some of its former regional lustre by acting as a mediator, whether in Gaza or in Sudan.

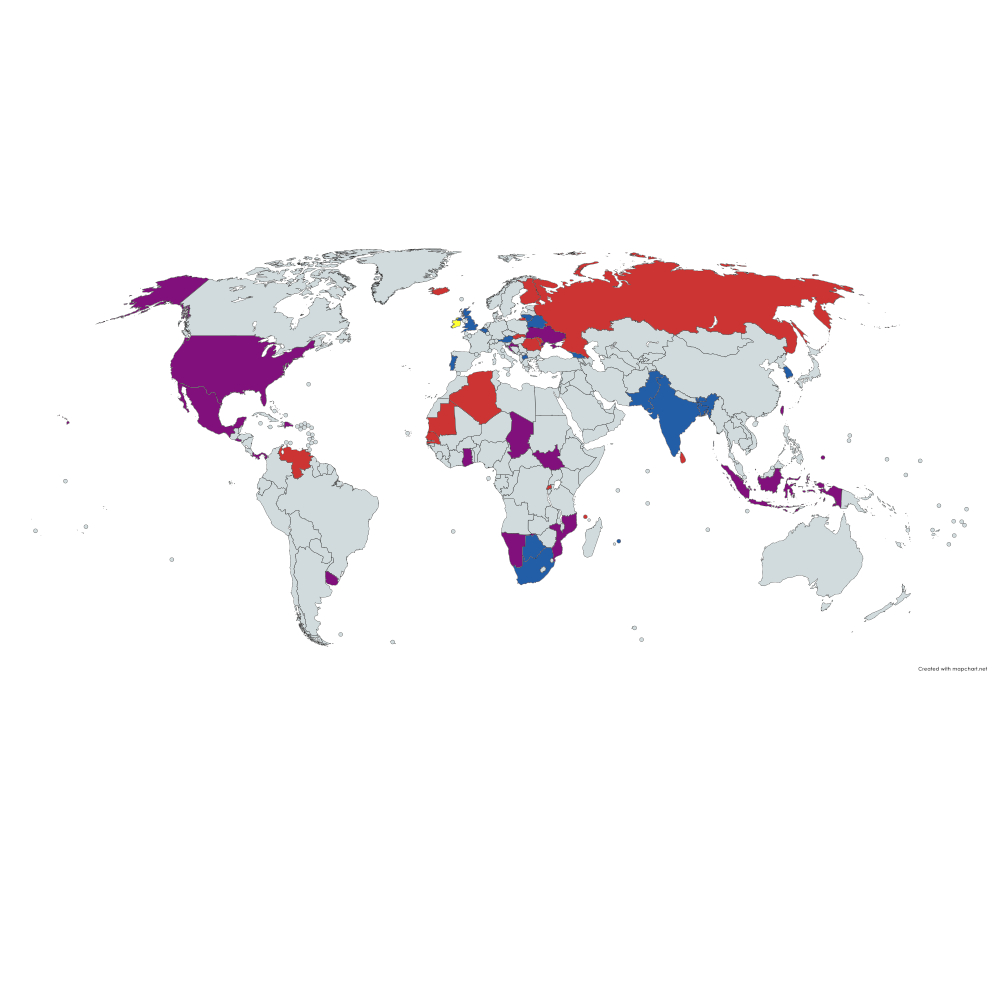

International dynamics: Western democratic countries struggle to maintain influence compared to China and even Russia. A Trump victory in the US elections would change American foreign policy, make solving the Iranian nuclear file impossible, and could lead to adverse reactions from what is now a nuclear-threshold state. Israel would be given free rein in the Occupied Territories; the Gulf states would be forced to choose sides.

Economic issues: The region remains an energy powerhouse difficult to ignore. OPEC+ arrangements will hold, and Gulf sovereign wealth funds might reconsider their asset allocation if G7 countries decided to seize – not just freeze – Russian foreign assets.

Policy Implications

Europe needs to confront China and Russia in the region, prepare for a possible Trump victory, and rein in the Israeli far right. Energy transitions may offer opportunities for regional collaboration. Sanctions against Russia and Iran need to be clearly communicated to other oil exporters unless they are spooked by financial weaponisation and refrain from investment in European capital markets.

Who Will Run Gaza?

Egypt administered the Gaza Strip between 1948 and 1967, but never thought about claiming it as its own territory. The Gaza Strip has remained a hot potato ever since. In contrast to the West Bank, where Israel expands illegal settlements and has annexation plans, it has no such ambition in Gaza. In 2005 Israeli forces even withdrew, only controlling external access points.

Who will run Gaza after the arms fall silent? Israel does not seem to have a concrete plan, except for “destroying Hamas” – which has run the Gaza Strip for nearly two decades – and disconcerting mind games about ethnic cleansing by pushing large population segments out of Gaza. Whatever is meant by “destroying Hamas,” it is a task whose fulfilment is unlikely; one cannot militarily destroy an ideology with deep roots in an insurgent movement and the broader population.

The Israeli government has also ruled out that the ailing and corrupt Palestinian Authority could ride back into Gaza with the help of Israeli bayonets, a plan that the US administration has peddled. (Leaving aside the question whether the PA would either want or could even do that given its extreme weakness; its leader, Mahmoud Abbas, is 88 years old). Israel does not want to rule Gaza, but will have to if no other solution is found. It is still considered the occupying force by the UN and wants to have the freedom to intervene in the future to thwart any emerging security threat like the Hamas terror attack of 7 October.

The UN or Arab countries such as Egypt, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia are unlikely to step in. They would only potentially assist in the administration of Gaza if Israel was ready to provide a credible political solution to the Palestinian question, but the populist Benjamin Netanyahu government with its right-wing extremists such as Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir is unlikely to even contemplate such an idea. Running Gaza will be a daunting task. There is an escalating humanitarian crisis, and up to three-quarters of all houses are damaged or destroyed. Donors such as the Gulf countries and the EU will not be enthusiastic to provide reconstruction funds yet again if renewed hostilities and destruction are a distinct possibility.

Will the War in Yemen End?

In September 2023, direct negotiations in Riyadh between senior representatives of Iran-aligned Ansar Allah (also known as the Houthis) and high-ranking Saudi officials, including the Saudi minister of defence, raised hopes about a pending end to the protracted war in Yemen, which has caused one of the world’s largest humanitarian crises and an estimated 377,000 deaths since its onset in 2015. On the verge of Christmas, then, UN Special Envoy to Yemen Hans Grundberg announced that Ansar Allah and the Saudi-backed internationally recognised government had committed “to a set of measures to implement a nationwide ceasefire,” proclaiming that he “will now engage with the parties to establish a roadmap under UN auspices [towards lasting peace]” (OSESGY 2023). While these are significant developments that bear the potential to end the stalemate in one of the deadliest regional conflicts, one should exercise caution when assessing the prospects for peace in Yemen any time soon.

Bent on terminating its direct involvement in the war, Riyadh failed to exact meaningful concessions from Ansar Allah. Instead, it demanded major ones from its Yemeni allies in the Presidential Council – who, given their dependence on Saudi Arabia, grudgingly acquiesced. With the Council representing a mixed bag of rival groups, however, upcoming negotiations will be challenging. Even if its members come to terms with Ansar Allah under Saudi pressure, the odds are high that intra-Yemeni fighting will be resumed thereafter – even if on a more modest scale.

Another obstacle to peace is Ansar Allah’s growing involvement in the Gaza War. Since mid-October 2023, the group has been launching missiles towards southern Israel. In mid-November, it also began to attack shipping lanes in the Red Sea. These attacks not only threaten to derail the upcoming intra-Yemeni negotiations (Lackner 2023) but also, and crucially, boost the risk of Yemenis being drawn into another major conflict.

Authoritarian Elections in the MENA: What For and Who Cares?

Around the world, 76 countries will hold elections in 2024 – a number of them situated in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region (The Economist 2023). Despite the prevalence of authoritarian tendencies and the failure of democratic transitions in many countries of the region, respective leaders seem to remain committed to practicing one key element of democratic systems at least: holding elections.

Iranians will head to the ballot box in March 2024, for the country’s legislative elections. Concentration of political power within the hands of a small elite and the oppression of opponents have intensified over the past few decades in Iran. This has led to a widespread loss of confidence there in electoral processes, demonstrated in low voter turnouts in recent years. Meanwhile, Algeria is due to hold the country’s second presidential election since Abdelaziz Bouteflika stepped down in 2019 after 20 years in office. Hirak, the Algerian civil protest movement pivotal to the ousting of Bouteflika, has largely rejected the current president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, as he is perceived to be a continuation of the previous political apparatus. As the opposition has called for boycotting previous elections in 2019 and 2021, we can expect low voter’s turnout in the upcoming elections again. In Tunisia, December 2023 marked the country’s first local elections under the new constitution, with a reported boycott rate of 90 per cent (El Atti 2023). Ennahda, the country’s main opposition group, has strongly questioned President Kais Saeid’s legitimacy since he suspended parliament in 2021 and called for boycotting the elections. Even in Libya there have been hopes that parliamentary and presidential elections, previously postponed for years on end, might be finally held in 2024.

While voter-turnout rates are expected to be low in Iran, Algeria, and Tunisia, underscoring their contested legitimacy, the opposite can be expected for Turkey. The local elections set for March will serve as a litmus test for the political fate of this polarised country. Following President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s re-election in May 2023, the Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP) aims to reclaim major metropolitan municipalities, currently held by the opposition. Istanbul’s mayoral election holds particular importance, both economically and symbolically, as the office of mayor marked the starting point of Erdoğan’s political career. If incumbent opposition mayor Ekrem Imamoğlu is re-elected, he may have a chance of winning the next presidential elections in 2028. Conversely, a victory for AKP candidate Murat Kurum could demoralise the fragmented opposition further and consolidate the authoritarian regime long-term (Turkey recap 2024).

Why are the MENA’s authoritarian governments, despite their electoral engineering often determining the results ahead of time, so determined to hold elections?

Authoritarian regimes across the region have adopted a narrative that seeks to justify various aspects of their conduct, such as violent crackdowns, oppression, and corruption. Democratic institutions like national elections are a useful element in legitimising such a narrative, portraying political leaders as democratically elected and their actions as in accordance with the will of the people.

Elections are a useful tool to draw clear boundaries to political participation. Incumbent leaders tend to put processes in place that push opponent groups out of the race. Such processes may take place in the form of vetting or the criminalisation of opposing political views. This allows authoritarians to maintain the concentration of power in the hands of the ruling elite by limiting the participation of other interest groups.

Elections are a means for consensus-building within the established system of rule. Military and paramilitary interest groups are integral players in elections held in the MENA region. Concentration of power in the hands of authoritarian ruling elites is achieved through collaboration between the military apparatus and civilian elements of the political elite. As such, elections are also a useful tool to help renew the consensus achieved between senior military and civilian leaders.

Egypt: From Mediator to Regional Power Broker?

In the past year, Egypt has played a major role in conflict mediation and provided humanitarian lifelines in Sudan, Libya, and Gaza. Acute risks to regional stability from these three wars fuel existing security threats through volatility, insurgencies, and arms trafficking the longer they go on. Managing these closely intertwined conflict environments puts Egypt on track to become a major power broker in the MENA region and the Sahel at a time when its battered economy weighs heavily on its foreign influence.

Libya and Sudan were major junctions in trans-Saharan arms trafficking long before the ongoing civil war in Sudan started in April 2023. Militias operating near the Libyan border with Chad transport military equipment, personnel, and fuel throughout the region, while weapons smuggled from Yemen and Eritrea via the Red Sea supply insurgents operating on the Sinai Peninsula and in the Levant. Murky battlegrounds also facilitate Russia’s advances into Africa, as both Sudan and Libya buttress revenue streams for Moscow and the Wagner Group. The US and UK’s recent airstrikes on Houthi targets to secure Red Sea shipping lanes marks a new escalation in the Israel–Hamas war with far-reaching implications.

Through 2023, Egypt engaged in multiple summits to broker humanitarian ceasefires via the UN, African Union, Arab League, Intergovernmental Authority on Development, and the US–Saudi-led Jeddah process in Sudan (Skinner 2023). It hosted several conferences in Cairo to facilitate a new roadmap between Libya’s rival administrations, and dialogue among Sudan’s highly fractured civil society. Though it initially suspended its mediation in the Israel–Hamas conflict after the latter’s second-in-command, Saleh al-Arouri, was assassinated in Lebanon, Egypt resumed its involvement only days later.

While countries rally around assisting in ceasefire and hostage negotiations between Israel and Hamas, or conflict management in Libya and Sudan, diplomatic rifts have strengthened in the Middle East. Egypt has so far benefitted from both trends in different ways. In the Israel–Hamas war, its indispensability opens the door for the expansion of political and economic collaboration – as, for example, through planned cash deposits from the Gulf, or US cooperation despite the recent straining of American–Egyptian relations. The fronts are more pronounced in Libya and Sudan, most notably with the UAE’s meddling in both countries through sponsoring and supplying militias with weapons, leaving Egypt as a more consistent mediator. For better or worse, Egypt’s proximity to three wars simultaneously is as much a security liability as it is a diplomatic opportunity to assert itself. Whether it can ascend from its role as mediator to a power broker, however, remains as open as these conflicts themselves do.

Will Syria’s Regional Re-Integration Continue?

During its annual summit on 19 May 2023, Syria under President Bashar al-Assad was re-admitted into the Arab League as a full, regular member. This was a major diplomatic and symbolic achievement for the dictatorial government in Damascus after being ousted for almost 12 years because of its massive, almost indiscriminate, repression of its own population in the incipient phase of the Syrian civil war in fall 2011 – a process that worsened in the years to follow, leading to hundreds of thousands of deaths and over 13 million displaced Syrians. The next regular Arab League summit, to be held in Bahrain in April or May 2024, will be a litmus test for whether Syrian regional re-integration will continue and what it might look like in concrete terms.

So far, Arab countries’ normalisation of relations with Syria since the 2023 Arab League summit has been without any substance, essentially yielding zero benefit for the regional governments who were previously opposed to the Assad regime. There has been no economic investment from the Gulf countries, and trade with Jordan or Egypt has remained minimal. In the short-term, at least, there has been no “normalisation dividend” to speak of. In addition, the diplomatic normalisation with Assad has not led to any improvement in border security or to a decline in drug smuggling, especially of Captagon and hashish, into Jordan and towards the Gulf countries. Rather, 2023 was a record year for documented drug-smuggling activities as well as increased use thereof by Arab youth in Syria and its neighbouring countries.

What is worse, the Assad government has instrumentalised the massive escalation of violence in Israel and the Occupied Territories since 7 October 2023 in two ways: Rhetorically, Assad and other Syrian officials have continuously denounced the Israeli aggression against Palestinian civilians while declaring that they have not been involved in any of the activities of the so-called resistance axis, thereby trying to improve their tarnished image in the region and beyond. Militarily, Assad’s armed forces have led a massive campaign against the Islamist opposition-controlled Idlib region, specifically targeting civilians. In the three months since October 2023, 200 people, mostly children and women, have been killed and over 120,000 internally displaced – happening out of sight and out of mind vis-à-vis Arab and international audiences alike (Haid 2024).

Will Iran Go Nuclear after a Trump Victory?

During his 2016 presidential campaign, Donald Trump criticised the Barrack Obama administration’s conclusion of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) in July of the previous year. Once in office, in May 2018, the Trump administration unilaterally withdrew from the agreement. The current Joe Biden administration has since unsuccessfully tried to revive the deal; Iran, claiming it is no longer bound by the JCPOA’s provisions either, has since resumed its uranium enrichment. It is now within breakout capacity (Millington 2022).

During the current presidential primaries, Trump, who will be Biden’s most likely opponent in the 2024 elections, has again called for a tougher stance on Iran. The higher (nuclear) stakes and Trump’s record of a “maximum pressure” policy towards Iran have raised fears of a potential military conflict should he win a second term in office in fall 2024. While such scenarios are not impossible, their likelihood is overstated in political commentaries.

The US’s sanction and embargo policies against Iran have been a constant of the two countries’ relations since the Islamic Revolution of 1979. When a 2003 report by the International Atomic Energy Agency found that Iran was in violation of its safeguards agreement, the issue escalated further. Subsequent US administrations have initiated several new rounds of international sanctions against Teheran – with the stated goal of preventing an Iranian nuclear bomb and a potential arms race in the Middle East. This international pressure eventually brought a new moderate Iranian government to the negotiation table in 2013, resulting in the “nuclear deal” reached between the P5+1 and Iran in Vienna in 2015.

However, neither the JCPOA nor its discontinuation have altered the fundamental parameters of the four decades and counting of US–Iranian antagonism. It only temporarily shifted the focus from military posturing towards diplomatic avenues. Even Obama, who championed a new approach “based on mutual interests and mutual respect,” continuously stressed that military options remained on the table. The Trump administration, on the other hand, shied away from limited strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities, let alone an open military conflict with Tehran, despite its “maximum pressure” approach culminating in the targeted killing of Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani in January 2020.

With these fluctuating tactics, the chances of escalation remain real – whether triggered by an emboldened second Trump administration ordering a pre-emptive strike, an Israeli spoiler play, or Teheran’s conclusion that going nuclear while still under political cover from Russia is the best way to counter an unpredictable US president. In a more favourable scenario, there might be continuity on the American side despite rhetorical grandstanding. Iran could also decide that flaunting its nuclear-threshold status may give it as much leverage as actually crossing the threshold – with considerably less risk.

Will the Abraham Accords Survive the Gaza War?

The Abraham Accords, signed in 2020 between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain, and later Morocco and Sudan, led to diplomatic normalisation and envisaged cultivating deeper economic, cultural, and technological ties between the respective countries. After the peace agreements reached with Egypt in 1979 and Jordan in 1994, four other Arab countries now entertain diplomatic relations with Israel. Saudi Arabia was rumoured to be set to join their ranks before the Hamas attack on October 7 scuppered that. However, Israel’s ongoing hostilities in Gaza and the unprecedented humanitarian crisis there have sparked concerns about the durability of these accords and the broader trajectory of Israel’s normalisation process in the region.

Arab governments that signed normalisation agreements with Israel are facing growing scrutiny and calls for accountability at home, exemplified by citizen-driven initiatives like protests, marches, and online activism. Up to 85 per cent of the population in Gaza have been displaced, and South Africa has launched procedures against Israel at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in the Hague over accusations of genocide. The vast majority of MENA populaces vocally support the Palestinian cause. Their governments are afraid that pro-Palestinian protests could turn against them in a re-iteration of the Arab Spring and threaten regime survival. This mounting pressure from below has led governments, such as those in Bahrain and Jordan, to recall their ambassadors from Israel, while US-brokered talks between Israel and Saudi Arabia have been suspended.

The Abraham Accords came with considerable incentives: The US took Sudan off its list of terrorism-sponsoring states, removed sanctions on it, and also recognised Morocco’s sovereignty over the entire Western Sahara territory. The UAE and Israel have a common interest in high-tech and defence investments, as well as in countering Iran’s regional posturing. The latter was also a major factor in the negotiations between Saudi Arabia and Israel. But the premise of the accords – namely, that sustainable normalisation could be achieved while ignoring the Palestinian question – has proven the populist right-wing Netanyahu government to be misguided.

The enduring criticism of the US for its perceived lack of impartiality in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict could tarnish its role as a mediator, potentially affecting its ability to encourage other Arab nations to establish ties with Israel. By signing the Abraham Accords, elites’ political and economic interests took precedence over the concerns and aspirations of their broader publics. Popular discontent remains a powerful social force, compelling governments to re-assess and reconsider these commitments – as seen in the recall of ambassadors, and underscoring the limitations of elite agreements.

China In, Europe Out?

China–Middle East relations will continue to deepen on two fronts in 2024. Geoeconomically, China’s influence in the region has grown in recent years in various sectors due to its Belt and Road Initiative, while the EU’s – and US’s – regional presence has been in relative decline. According to Chinese customs data, the volume of trade between itself and the Middle East nearly doubled between 2017 and 2022, from USD 262.5 billion to USD 507.2 billion. By 2023, China was the leading import and/or export partner for most countries of the region. For example, it replaced the EU as the Gulf Cooperation Council’s top trading partner in 2020. Key sectors in China–MENA relations include traditional energy, renewable energy, infrastructure, technology and communications (including Huawei’s 5G), fintech, and manufacturing.

Geopolitically, two points are worth noting. First, China will continue its policy of non-interventionism. The expensive regional military order is dominated and financed by the US. From the perspective of own national interests, there is no reason why China should change this equation. In 2024 the US will continue to spend more geopolitical resources regionally (thanks to the Gaza War), with China being the biggest economic beneficiary.

Second, regarding the “geo” in geopolitics, the region is undergoing a slow pivot away from “the West” and self-identifying with other geographic imaginaries such as “Asia” and the “Global South.” In bilateral and multilateral exchange formats with each other or with Chinese, Indian, and other Global South partners, regional officials are increasingly dropping the term “Middle East” in favour of “West Asia.” They are slowly shedding the Western-centric concept of “the Middle East” (and “Near East”), reconceptualising the region’s geographic identity in a post–Western order world (Forough 2022). Another sign of this trend in recent years is countries of the region actively seeking membership in Asian-led institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, and BRICS+. Moreover, the Western powers’ unapologetic support for how Israel has pursued its war in Gaza is going to speed up the regional distancing from the West. MENA countries have been supportive of South Africa’s case at the ICJ, while China has called for an immediate ceasefire and full Palestinian statehood within the framework of a two-state solution.

Will OPEC+ Hold?

The Saudi-led OPEC and Russia have not been natural allies historically. During the Arab Cold War from the 1950s to 1970s, they saw each other on opposing sides of the ideological divide, with the Soviet Union supporting revolutionary regimes in the Middle East that were hostile to the Gulf monarchies. The Saudi decision in 1985 to stop cutting production and open its oil spigots to regain market share led to collapsing prices. The fiscal impact of this decision on the USSR played no minor part in its eventual demise a few years later.

All the more surprising was this odd couple joining forces in 2016. Russia became a member of OPEC+, which agreed to cut oil production. Before a glut caused prices to decline from 2014 onwards, Saudi Arabia had tried to instigate a price war against the newly emerging producers of unconventional tight oil in the US and lost. Yet, the new-found unity between the two oil heavyweights lasted only so long. In early 2020, Saudi Arabia and Russia engaged in a brief price war with each other, before agreeing on renewed OPEC+ production cuts in April of the same year. The US welcomed this step at the time. US producers were facing bankruptcy as the COVID-19 pandemic obliterated oil demand, pushing wholesale prices at the oil-trading hub in Cushing, Oklahoma, into negative territory at one point.

In October 2022, OPEC+ countries cut oil production by two million barrels per day – their first production cut since 2020. This time, the Western powers were outraged that the Gulf countries would collaborate with Russia in the middle of the latter’s war of aggression against Ukraine. However, the Gulf countries have their own national interests. They see opportunities in exploring new partnerships in an increasingly multipolar world. They need to safeguard their fiscal stability and fund development projects for the post-oil age. By the mid-2030s, global oil demand could level off – as, indeed, Saudi Aramco warned in its 2019 IPO prospectus.

How will OPEC+ fare when OPEC meets next, in June 2024? All cartels are inherently unstable. Free riders try to benefit from higher prices without maintaining quota discipline and cutting production, like Iraq did during the Arab oil boycott of the 1970s. And then there are the newcomers, encouraged by artificially high prices. If the reduction in oil production in OPEC+ countries continues, the partially lost volumes may be compensated for by increased production in non-OPEC ones such as the US, Canada, Guyana, and Brazil. Traditional producers from the Middle East would lose market share like they did in the early 1980s. Energy transitions will likely impact on oil demand in the medium- to long term as well. If history is a guide, OPEC+ will then falter – albeit in June 2024 it might still be successful in keeping its cartel together for now.

How Would Gulf Sovereign Wealth Funds React If the West Seized Russian Assets?

Western countries have taken the unprecedented step of freezing USD 300 billion in Russian assets in the wake of the latter’s ongoing war of aggression against Ukraine. Now the G7 wants to discuss at its next meeting in February 2024 going a step further, namely by seizing those assets and using them to pay for restoration work in Ukraine (Tamma and Politi 2023). This is ringing an alarm bell with sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) in the Gulf countries and China, given they hold significant assets in Western capital markets and jurisdictions.

The investment authorities of Abu Dhabi, Kuwait, and Qatar belong to the largest SWFs worldwide. More recently, Saudi Arabia has developed its Public Investment Fund into and internationally active investor, rendering it completely different from the passive investor and sleepy holder of domestic assets that it was only a few years back (Roll 2019).

The very term “SWF” was only coined in 2005 at the time of the second oil boom. Gulf SWF assets have since swelled. During the financial crisis of 2007/8, they often acted as white knights for Western banks and companies facing financial turmoil. Heavy investment was thus made in companies such as Deutsche Bank, Barclays, and Volkswagen.

The US, with the help of other Western countries, has increasingly weaponised the global financial infrastructure such as the SWIFT payment system (Farrell and Newman 2019). The Gulf countries have not been targeted by Western sanctions like Iran and Russia have, but they have faced such threats in the past. During the Arab oil boycott of the 1970s, the US even threatened to inflict a unilateral food embargo on the import-dependent Gulf countries (Woertz 2013). Against this backdrop, the threatened seizure of Russian assets will likely prompt them to diversify assets away from Western markets. They have already increased the share of emerging markets in their portfolios. The year 2023 also saw increased gold purchases by sovereign entities. So-called petrodollar recycling was a crucial aspect of international financial stability during the oil booms of the 1970s and early years of the new century, but this continuing to happen cannot be taken for granted in the future.

This GIGA Focus deviates from the series’ typical format. It is the joint product of several GIGA Institute for Middle East Studies staff members. Eckart Woertz contributed the section on the administration of Gaza after the war, Jens Heibach authored the part on the Yemen War, Mira Demirdirek and Sara Bazoobandi wrote the one on regional elections. Hager Ali addressed Egypt’s growing importance as a mediator, André Bank looked at Syria’s regional re-integration. Nils Lukacs examined the possible implications of a Trump victory on US policy in the MENA. Deema Abu Alkheir authored the section on the future of Israel’s normalisation process with some countries of the region. Mohamadbagher Forough analysed the growing importance of China regionally as Europe struggles to maintain its influence there. The parts on OPEC+ and Gulf SWFs were written by Eckart Woertz and Olena Osypenkova, who also jointly edited this GIGA Focus.